* Please note that due to the sheer amount of photographs used in this article, several of the picture frames are in slide show format that can be be stopped and started by hovering over the picture.

Cinemas in Chester even in the declining years of popularity in the 1970s had to strongly compete for their share of the audience. One very important quality required of a cinema manager was the ability to muster strong public relations, and support from local businesses, press, councillors, transport, publicans, etc., to put his cinema on the local map, to maintain, and expand the business. At the dawn of the 1970s, the Classic cinema, better known as the Tatler, had just closed, leaving the city with only two “super cinemas”. The huge superior two thousand plus seater ABC, and the Odeon situated in the prime position on the Town Hall Square. Both were still original single screen units. During this frenetic era, the Odeon was acknowledged to be the stronger of the two in achieving substantial admissions, regularly selling out it’s 1628 seats capacity. Within the Odeon circuit it’s gross take was envied by even the “key theatres”. It is with this background that when a new manager was to be appointed at this particular Odeon cinema, the regional manager would be inundated with the cream of applicants, all vying with the hope of becoming the successful applicant. So it came to pass that in 1974, with General Manager David Elliot being promoted to the key Odeon theatre in Edinburgh, Allan Rosser was duly appointed General Manager, having moved across from the Odeon Blackburn.

Staff member, the late Pamela Jones inside one of the fully animated hand painted displays in the circle lounge

It was clear from the outset that this manager had a driven determination not just to keep the cinema at its present lucrative position within the company but to push the boundaries even further. Allan achieved this quickly by involving all his management and staff to focus on maintaining the Odeon’s dominance in the city’s entertainment. He would regard admissions of under 800 customers a performance as a failure, and was only content when he could boast capacity admissions. No matter what source of competition he faced, his local opponents would give way gracefully (usually through gritted teeth), as they acknowledged that he was in a league of his own.

He was in a world of his own with the re-vamped Super Saturday Shows. I remember that I needed all my technicians on duty to cope with the demands with the complex lighting displays and stage features that Allan demanded. The children loved it, and in return he smashed all box office records for the children’s Saturday morning shows in the history of the building.

The two competing newspapers, The Cheshire Observer, and Chester Chronicle would be top heavy with their front pages dripping with pictures and editorial on the Odeon. Full pages of promotions, competitions offering prizes of holidays, cars and other high value items, even regular visits to Pinewood Studios that Allan would personally supervise. His flair for publicity was extraordinary

007 car at the Northgate Area

Whether it was James Bond’s cars or boats, giant Disney characters in street parades, massive hand painted displays, mermaids trapped on the River Dee, to Lady Godiva trotting around the city clad only with her long golden hair, his ideas seemed endless and achieved both local and national press coverage. Even the dressing of the front of the building for the Queen’s silver jubilee would be turned into a promotional news item.

Shirley Ellis out of costume

Shirley Ellis, who worked there at this time recalls “I remember being given the PINK PANTHER costume to wear and going across to the Top Rank bingo hall to draw the first number, then returning, and being chained outside the Odeon to promote the latest PINK PANTHER film, supervised by Allan’s assistant Tony Brooks. It was wonderful working there. It was pure fun, wasn’t like work at all”.

Getting floats ready for various parades would involve the staff voluntary starting work to dress them at 6am in the morning. The rewards for the staff was that they, and their families took part in the promotions, and then at the “after event parties” given as acknowledgement for their involvement.

The film that nearly BURNT the house down

Allan Rosser had to cope with such situations as numerous terrorist bomb alerts, operating a busy cinema with a meagre allowance of electricity each day due to industrial strikes, and when fanatical arsonists attempted to set fire to the building in protest to the screening of “The Last Tango In Paris”. The blaze resulted in the canopy being badly damaged costing many thousands of pounds to repair. It was stated that if not for the fast action of a passing policeman at 2am in the morning, the building would have been gutted.

It was under Allan’s tenure that the Odeon was transformed into a three screen cinema. Mainly because of the substantial amounts of money that the building was taking at the cash desk, the Odeon Board of Directors were persuaded to grant extra money to be spent at Chester which allowed the front circle to be extended down towards the screen, which made a splendid new 802 seat auditorium. Incredibly, the cinema remained open during this major alteration. Originally, in 1936, the builders engaged were a firm called Hamer. The foreman in charge of the tripling, by a strange twist of fate was a John Hamer (no connection). John worked tirelessly, completing most of the partitioning single handed. G F Holdings were the main contractor for the tripling. It was Holdings who fit out the new Cineworld recently at Broughton.

Now with three screens, Allan cranked up the PR pressure even more. He managed to get 100% PLUS from all of the staff to work with him. Many recalled that it was an exceptionally busy time packed with laughter, and good memories. Behind his light hearted manner lay a steely determination for success, The cinema thrived under his style of management.

JOYCE HODGKINSON with Terry Underhill at the opening of Santa Claus the Movie grotto

By nature Allan Rosser was a practical joker, you were always on guard as to what was coming next. I remember our head usherette; Joyce Hodgkinson leaving work at 9.30pm after a full days shift. As she trudged her long walk home to Handbridge, Joyce struggled with her shopping bag, she told me that she could not understand why her shopping seemed so heavy. At home all was revealed when she unloaded her bag to find there were three stow away house bricks placed there by courtesy of Alan Rosser!

Many colleagues who worked with him state that the Odeon was a fun place to work because of Allan. However, the serious side of heading the management team was the smoothness of the operation that was achieved, and attributed to him, and by placing Chester Odeon in a very secure financial position

Post Chester- Allan continued his promotions at The Drake (Odeon)

Allan Rosser was promoted to The Drake (Odeon), Plymouth in 1985, leaving behind many friends, and Chester Odeon with a firm base that carried it forward for a further twenty one years.

With all good wishes to Elizabeth and Allan who are enjoying retirement with their family in Devon.

* As this feature is to be placed on the Odeon page of the website, we would like to hear from you if you worked there at this time, or enjoyed just visiting the ODEON between 1974 & 1985 ~ the Allan Rosser years.

A line or paragraph would be much appreciated –

Peter Davies © chestercinemas.co.uk

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

THE STORY BEHIND THE UNIVERSAL TRADEMARK

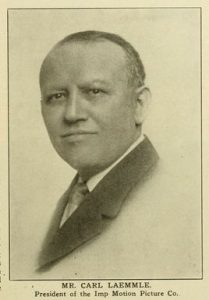

German born Carl Laemmle started his career in 1906 with a chain of nickleodeons. This was so successful that at the age of 39, he set up a company to distribute film. As this proved very lucrative, the 39-year-old set up a film distribution company which he named the Laemmle Film Service

A fast, forward thinker, he did not want to part with money to third party operators. Treading on many toes, including Thomas Edison’s General Film Company (of which he was an original member). He doggedly saw off 289 legal actions brought about by GFC from 1909-12 and was ultimately victorious. According to his niece, Carla Laemmle, Carl was at a loss as to the name to call his new company. As he gazed through the office window, a plumber’s truck went past with the name Universal on the side. Carl lifted the name and adopted it for his new company

Universal City would become the largest and most prolific studio in the world (eventually supplanted by MGM soon after its inception). Laemmle inaugurated the film career of Irving Thalberg, who started as a $35/week secretary in Universal’s New York office and quickly became head of its California studios. Universal lost Thalberg to MGM where he transformed their business into a powerful operation. Laemmle, the father of Universal Pictures, was reputedly the most good-natured and least neurotic of the studio bosses.

Watch this visual history of UNIVERSAL’S trade mark

Organized studio tours began in 1915 (they were discontinued in 1928 with the arrival of talkies, but resumed in 1964). Carl Laemmle died in 1939 of a heart attack in Los Angeles at age 72. Universal merged with International Pictures, an independent studio headed by ex-20th Century-Fox executives William Goetz and Leo Spitz in 1946, together with interested investments from J Arthur Rank, renaming it Universal-International Pictures. The main structure of the logo has remained throughout the years. Benefiting from digital production in later years, the logo remains one of the most recognized film trademarks, and certainly the most dramatic.

Organized studio tours began in 1915 (they were discontinued in 1928 with the arrival of talkies, but resumed in 1964). Carl Laemmle died in 1939 of a heart attack in Los Angeles at age 72. Universal merged with International Pictures, an independent studio headed by ex-20th Century-Fox executives William Goetz and Leo Spitz in 1946, together with interested investments from J Arthur Rank, renaming it Universal-International Pictures. The main structure of the logo has remained throughout the years. Benefiting from digital production in later years, the logo remains one of the most recognized film trademarks, and certainly the most dramatic.

chestercinemas.co.uk ©

Next month’s update continues the Trade Mark history of 20th Century Fox

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Many people, when watching a film don’t give a thought to all the hard work in bringing it to the screen. The continuity person, or script supervisor’s job is to make sure everything stays in continuity. A scene may take hours or days to shoot, with several camera angles used. It is the job of the continuity person to make sure everything looks the same, for example someone wearing the same tie, when shooting re-commences, for example the following day.

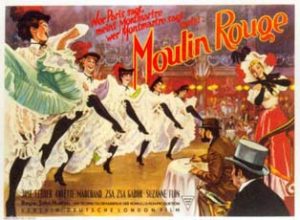

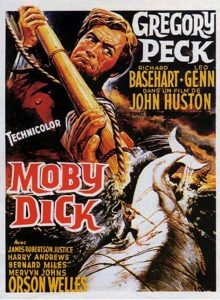

Angela Allen was born in Maida Vale, London, in 1929. The first film she worked on alone was Old Mother Riley, Headmistress (1950). She was awarded the MBE in 1996, a BFI Industry Award and the Michael Balcon Award in 2005. The Michael Balcon Award was presented by John Huston’s daughter Anjelica. Films she has worked on include The Third Man, The African Queen, Women in Love, Moby Dick, Moulin Rouge, The Man Who Would Be King and The Misfits, starring Marilyn Monroe.

What did you do after leaving school?

I went to work for a theatrical agency. I wanted to work in make up but back then one of the requirements was that you had to draw, and I was no good at that. I had heard of continuity and I thought I’d do that. I had learned shorthand typing, which was required for the job and started knocking on doors. My first job was at Isleworth Studios at the age of eighteen. My first film as assistant continuity girl was Night Beat (1947), followed by Mine own Executioner (1947). I was also an assistant on Bonnie Prince Charlie (1948). I went on to become the continuity girl on that picture because the lady left to get married.

You worked with director Carol Reed on The Third Man, what was he like to work with?

Carol Reed

Carol Reed was one of the best directors I ever worked with and I learned a lot from him. I think he was my greatest teacher. He was a brilliant technician – he knew how to make things match. You learned what you needed to look at and what you didn’t. I used to take notes to the cutting room for him, and that is where I learned a great deal about how you can change things. I think he was underestimated in England and in my opinion he was as great as David Lean.

The stopwatch is used in continuity – would you explain why it is used?

The stopwatch is one of the main ingredients of the job. Normally you get a script and have to time it. You haven’t seen the location or know who the actors are but you read and act it out around the house. You have to time the original script and all the versions that come after. Each has to be broken down and a progress report is made. This states what time the first shot was called, the lunch break and any hold ups that occur because something broke down. When continuity person Pam Francis and I started every shot had to be typed in detail. This included what lenses were being used. You had to record when the camera started to track, when it stopped and when someone stood up. The dialogue would be typed in red and the action and descriptions in black. When I started we didn’t have the Polaroid camera, we had to draw and I was an incredibly bad artist. We got the Polaroid around 1950.

You worked with director John Huston on fourteen occasions, what was he like?

John never lost his temper. On African Queen he trusted me when Katherine Hepburn argued about what she was wearing. I told her she would have to change and she said, “No, I don’t.” John said: “That is Angie’s job, we will go with what she says.” I didn’t find out for another six weeks if I’d done the right thing, which was nerve racking. Fortunately, I was right. David Lean’s continuity girl Maggie Unsworth once said to me, “One thing you mustn’t do if they ask you a question is dither, and if you make a mistake, admit it.” I have always thought that to be good advice.

Who offered you the job on African Queen?

It was Producer Sam Spiegal (1901-1985), who interviewed me for the job. He thought because I was the youngest continuity girl in the business at that time, I would be able to cope with working in Africa.

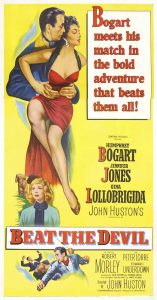

I hear Beat the Devil was a fun film to work on?

It was fun because you never knew what the story was going to be – everyday it used to change. We used to laugh so much when Robert Morley and Peter Lorre ad libed. Humphrey Bogart wasn’t an ad liber but the others were. It was a mad film; we never knew what the story was from day to day.

Finally, did you have a favourite location and studio?

I loved all the locations I have been to. My favourite is France. I first went there when I was given Moulin Rouge. I preferred location work to studio work as long as the location wasn’t in England. It was nice to travel abroad. My favourite studio was Shepperton.

David A Ellis © chestercinemas.co.uk

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Please feel free to share the videos on ![]() Our Facebook group is updated regularly………. PLEASE JOIN & LIKE THE PAGE, adding your friends too. This week saw the website reach 79% new visitors. Many thanks for those who have added their friends to the group, this is a tremendous help in establishing the site.

Our Facebook group is updated regularly………. PLEASE JOIN & LIKE THE PAGE, adding your friends too. This week saw the website reach 79% new visitors. Many thanks for those who have added their friends to the group, this is a tremendous help in establishing the site.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Next month’s update…….

Where did Oscar get the name ODEON from? You may be in for a surprise!

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________